Fake pills, real healing

(Lynch 2012)

Over the past decade, the impact of placebo responses has increased to the point of ruining multiple clinical trials – but only in the United States. As a result, drugs that reach the final trial stages appear to be less effective or ineffective when compared to the placebo.

“Everyone should know this stuff” Level

Placebos are sugar pills, sham surgeries, or fake medicine. The purpose of a placebo is to test the effectiveness of new drugs and treatments. A clinical trial’s success is measured by subtracting the placebo recipients’ reactions from those of the drug recipients (Kremer 2013). The remaining results are attributed to the drug.

Interestingly, many people who receive a placebo in a clinical trial have similar physical or psychological responses to those who receive the real treatment. This is called the ‘placebo effect.’

Until Dr. Ted Kaptchuk created the Placebo Studies Program at Harvard, there was limited research dedicated to the biological mechanics of this effect (Feinberg 2013). Based on his research there, Dr. Kaptchuk says the placebo effect occurs because brains are “prediction machines” (Harnett 2015). The brain recognizes that: (1) the body responds to pills, injections and surgeries, (2) quickly learns to predict that these treatments will always make pain go away, and (3) responds accordingly, even when the treatment is not real (Harnett 2015). So it has been commonly accepted that placebo effects are ‘mind over matter’ occurrences rooted in a brain’s will to react to perceived correct criteria.

Over the past decade, the impact of placebo responses has increased to the point of ruining multiple clinical trials – but only in the United States (Kremer 2013). As a result, drugs that reach the final trial stages appear to be less effective or ineffective when compared to the placebo (Kremer 2013). Because the placebo effect’s impact has grown, some drugs that have met FDA standards in the past would not meet them today (Stahl 2012). Pharmaceutical companies may not realize the affect the placebo effect has had on their drug development (Stahl 2012).

Years of research and technological breakthroughs have helped to understand the placebo effect. No single factor is responsible for the body’s specific reaction to a placebo. Factors include doctor-patient interaction, setting, and expected outcome (Feinberg 2013). Many believe that the duration, perceived funds, and advertisement time dedicated to a trial indicate to patients that they will have a successful treatment (Marchant 2015). To visualize this, Dr. Mogil, Head of the Pain Genetics Lab at McGill University, compiled data from pain medication trials all over the world going back over 20 years (Marchant 2015). Mogil believes these factors explain why only American trials, the only ones that tend to be grander in all aspects, have seen a steady increase in placebo responses while the level of placebo responses in all other countries’ trials have remained consistent (Marchant 2015).

Linking placebo responses to genetics, Kaptchuk’s team began discovering in 2012 that some people have a genetic alteration that makes placebos follow a similar neurological path as a real treatment (Prescott 2015). These genetic markers were aptly named, “placebomes” (A play on the word ‘genomes’ – the collective set of genes in an organism) (Prescott 2015).

Although the existence of the placebo effect is a widely accepted medical fact, its power is not widely acknowledged. It has been difficult for those like Kaptchuk, who believe it is a doctor’s responsibility to “use every tool in the box,” to convince the medical community to accept the placebo as a type of treatment (Feinberg 2013).

“For geniuses only” Level

The leading scientists and medical professionals involved in these findings hope their information will advance treatment procedures and patient care by taking advantage of this new understanding of how the body heals itself (Stahl 2012). But progress has been slow, especially in the US.

In 2012, American studies showed that antidepressants for the mild to moderately depressed only had significant benefits on 14 percent of patients (Stahl 2012). This fact led Kaptchuk and Kirsch to find that benefits significantly increased when these types of patients took placebos (Stahl 2012). After all, as Kirsch explained, the reason the 14 percent got better was mostly because of their placebo effect to the pills (Stahl 2012). A similar discovery in England led Dr. Ted Kendall, director of the National Center on Mental Health, to spearhead a policy shift towards treating mild depression with placebo effect inducing ‘talk therapy’ (Stahl 2012). Back in the United States, mainly psychiatrists like Dr. Michael Thase, professor at University of Pennsylvania, formed the counter argument, stating that Kirsch’s studies neglected to account for “the benefits to individual patients” (Stahl 2012). The way he sees it, antidepressants “help 14 percent of patients” and he “[wishes] antidepressants were stronger” (Stahl 2012).

Though change in the impact of the placebo effect is clearly occurring, there remain members of the medical world conditioned to believe that better medical care is synonymous with pushing more medication, despite the fact that the vast majority of mildly depressed patients receive “virtually no benefit from the chemical in the pill” (Stahl 2012).

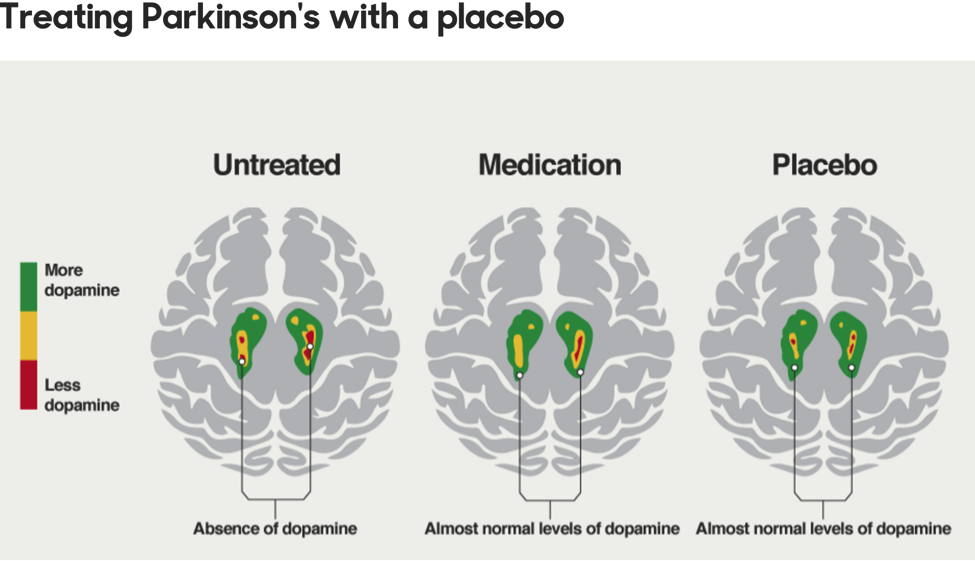

Through the Harvard program, Kaptchuk and his coworker Dr. Irving Kirsch have been collecting data proving that although placebos cannot cure cancer, they work just as well as actual treatments such as vertebroplasties, mammary artery ligations, arthroscopic surgery, and acupuncture for migraines (Newman 2014). They also work along similar chemical pathways in the brain as antidepressant and Parkinson’s medications (Feinberg 2013). That is to say, the brain alone can both heal horrible ailments and spare patients the adverse side effects and major expenses.

(Fong K.)

The reasons the brain makes certain connections are hard to definitively identify because placebo effects are responses to “a sum of variables” which differ for many people (Feinberg 2013). Determined to pinpoint the factors required to elicit a placebo response, Kaptchuk and Kirsch’s team proceeded to isolate and study one possible factor at a time (Feinberg 2013). In the 2000s, they studied patient care. The idea being that, based on the amount doctor-patient interaction (physical contact, attentiveness, and displays of emotion) patients would have a stronger placebo effect (Feinberg 2013). It worked.

As technology advanced, so did the studies. In 2012, Kaptchuk and Kirsch’s lab found the biological explanation for the placebo effect in some people. Research fellow, Dr. Kathryn Hall, used genome sequencing technology to locate the first placebo biomarker, ‘catechol-O-methyltransferase’ or COMT, which influences dopamine release in response to a placebo treatment (Prescott 2015). This first discovery enabled the group to review the past decade of published scientific work and identify even more genetically influenced placebo responses (Prescott 2015). Though they are just beginning to map out the affected neurotransmitter pathways, they have already found biomarkers along opioid and serotonin pathways, which relate to depression (Prescott 2015). Their research has found that because the placebo pathways are the same as drug pathways, drug responses influence the placebo effect and vice versa (Prescott 2015).

They just may be the means to “transform the art of medicine into the science of care,” as Kaptchuk has been trying to do for decades (Feinberg 2013). He envisions this newfound understanding of the brain’s innate healing abilities to modify clinical trials and how we medicate illness (Prescott 2015).

Impress your family and friends with these three related fun facts:

Fact 1: Placebo is Latin for “I will please,” as in, “I will please the Lord,” which was what mourners said after a priest spoke at funerals (Kremer 2015). This became the term used to describe hired mourners and those who came for the free food, both of whom were seen as inauthentic (Kremer 2015).

Fact 2: America and New Zealand are the only countries allowed to directly advertise medicine to patients (Merchant 2015).

Fact 3: It takes a little over a decade to develop a new drug to market-ready stage (Anderson 2014).

Author: This page was created by Keziah Clarke, a senior at Choate Rosemary Hall in Wallingford, CT. Keziah’s spirit animal is the sloth. Someday, Keziah’s fame will be the result of being the first 4 Michelin Star rated chef. Her food will be so good the guide will create an entirely new level of delicious for her.

Works Cited

Feinberg C. (2013.) The Placebo Phenomenon. Harvard Magazine. http://harvardmagazine.com/2013/01/the-placebo-phenomenon

Fong K. How can a dummy pill have a real affect on your body? BBC iWonder. http://www.bbc.co.uk/guides/zq8mhv4

Harnett K. (2015.)The Placebo Effect Grows (but only in the US.) Boston Globe. https://www.bostonglobe.com/ideas/2015/10/16/the-placebo-effect-grows-but-only/vvj3f4eEC3GNv6wrcvYARP/story.html

Kremer W. (2015.) Why Are Placebos Getting More Effective? BBC Magazine. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-34572482

Lynch E. (2012.) Maximum Strength Placebo. LaughingSquid. http://laughingsquid.com/maximum-strength-placebo/

Marchant J. (2015.) Strong Placebo response Thwarts Painkiller Trials. Nature. http://www.nature.com/news/strong-placebo-response-thwarts-painkiller-trials-1.18511?WT.mc_id=TWT_NatureNews

Newman D. (2014.) Placebo Surgery : More effective than you think? Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-h-newman-md/placebo-surgery_b_4545071.html

Stahl L. (2012.) Treating Depression: Is there a placebo effect? 60 Minutes. CBSNews. http://www.cbsnews.com/news/treating-depression-is-there-a-placebo-effect/

Prescott B. (2015.) The Placebome? Harvard Medical School News. https://hms.harvard.edu/news/placebome

Leave a Reply